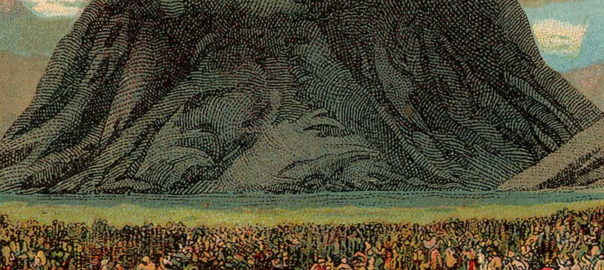

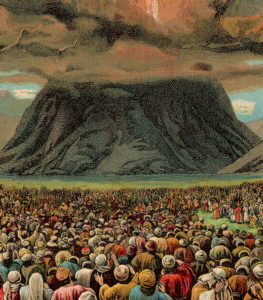

In the story we tell each other, Jews* left home because of a famine, lived for generations as guests and then slaves in a land not theirs, escaped — or, arguably, were expelled as scapegoats after a series of catastrophes — and traveled for weeks into an adjacent wilderness to camp at the foot of a mountain for nearly a year.

The mountain has many names, but for a long time now is most often alluded to as Sinai. While camped, the people entered into that covenant with the One (known in English as God) which remains, for us, the index of our identity.

We tell each other that each of us, in every generation, is obligated to see oneself as if having personally participated in this exodus. And we provide two supporting assertions.

One is neatly material, rational, an argument recited with the story at Passover: had the One not extracted our ancestors, their descendants (including us) would still be slaves — and, by implication, absent our Covenant, not Jews the way we understand that to mean.

The other assertion is something else entirely: diffuse, fragmentary. We tell each other that, at least at the moment of the establishment of our Covenant, not only the contemporary descendants of Jacob-called-Israel stood at Sinai: rather, every Jew who will ever live. So our Covenant is not an inheritance alone; each of us was there to hear, to learn, to swear.

This other assertion shifts the event, and our Covenant, and us out of time. It needn’t be, in this view, an event that ever happened — because it is always happening. People joining the tribe without having been born into it are always already there. And, critically: the Torah, that Teaching of the One delivered alongside our Covenant, is not only any of the record left to us by prior Jews; each of us stands at Sinai, at every moment in earshot of the thunder.

Hear, o Israel! Does any one of us catch every syllable? Does any one of us listen with all one’s limited attention at every moment? But because we live in time, we have available to us each moment to choose to listen, to compare what we hear with what we heard before, with what others hear. And though we carry the record as whole as we can, we may find it mistaken without making it any less sacred.

What this means for any who have translated, paraphrased, or been inspired by our record is for them to consider.

* In the story, at the time Jews (as Judah) comprised one of 12 (or so) tribes, all Children of Israel. By the time the story starts to line up neatly with history and archaeology, most of the other tribes were separate from Judah. Their descendants, the Samaritans, would also fall under this umbrella. But, as a group, their view of Torah is different, and I won’t put words in their mouths.